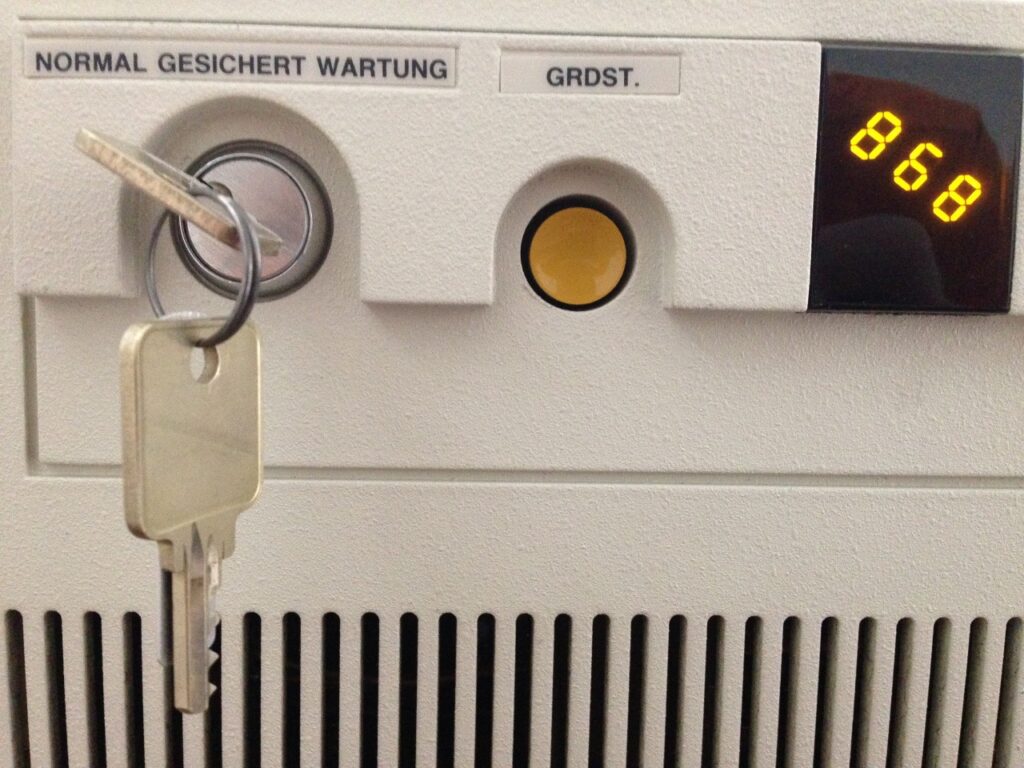

Von den Leuten, die uns “STRG”, “ENTF” und “EINFG” gebracht haben, ein Highlight, das sich leider nie durchgesetzt hat: Die GRDST-Taste.

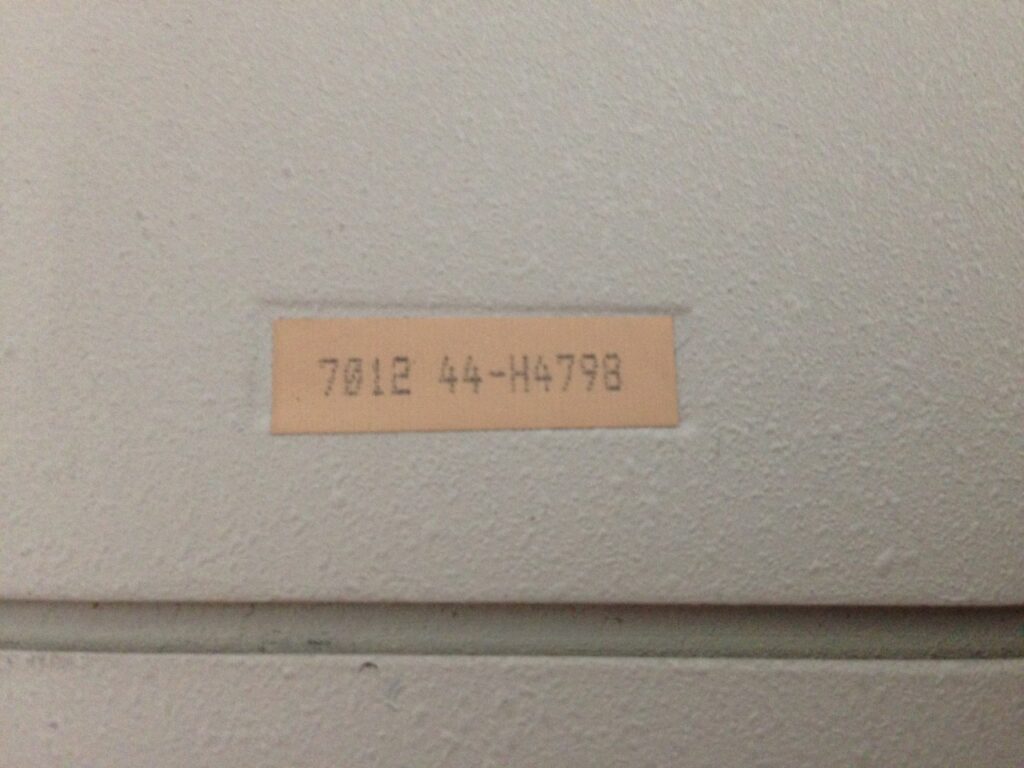

Diese RS/6000 hat den Weg zu mir so um 2000 gefunden, als mein erster Vollzeit-Linuxjob noch ein paar Jahre entfernt war.

Damals kuschelte IBM etwas widerwillig mit Linux und hatte auf AIX 4.3.3 parallel zur Einführung von AIX 5L (das L sollte für die Nähe zu Linux stehen) RPM als additiven Paketmanager eingeführt. Die Liste der damals verfügbaren Pakete kann bei bullfreeware.com bewundert werden (hier ein lokaler Mirror). Ich habe zuletzt noch einige davon installiert, um das Tool zum Benchmarking übersetzen zu können.

Zur 7012 besitze ich auch noch das passende SCSI-CDROM mit der passenden obskuren Blockgröße. Installationsmedien sind aber keine mehr vorhanden. Die Demo-Installation mit User root und Password root muss also für immer halten. Außer AIX ist mir kein Betriebssystem bekannt, das auf dem System nutzbar wäre.

SSH fehlt, aber per Telnet über den wackeligen AUI-Transceiver mit 10 Megabit/s macht das System einen sehr guten und responsiven Eindruck, fast besser als heute manche VMware-Instanz. 😉

Die Towers of Hanoi aus dem BYTE Unix Benchmark führt die RS/6000 mit ca. 1050 Loops pro Sekunde aus. Ein halbwegs aktuelles Vergleichssystem mit Intel-CPU und 3,6 GHz kommt auf ca. 3200000 Loops pro Sekunde.

Divisionen in der folgenden Schleife macht die RS/6000 mit 16500/s (Perl 5.5 vorinstalliert) bzw. 14500/s (Perl 5.8 aus dem RPM); mein moderneres Vergleichssystem kommt auf knapp 7 Millionen/s.

perl -e '$o=time();$s=$o;while(10>$o-$s)

{rand()/(rand()+1);$i++;$n=time();if($n!=$o)

{printf"%i\n",$i;$i=0};$o=$n}'

Softwaretechnisch größtes Highlight dürfte das installierte Java 1.1.8 sein. IPv6 wird zur Konfiguration angeboten, funktioniert aber in dieser aus dem Jahr 1999 stammenden Implementation nicht wirklich zufriedenstellend.

Technische Daten: POWER1-Prozessor mit 50 MHz, 128 MB Arbeitsspeicher, 2 GB Festplatte. Produktionszeitraum 1993-1994. (Mirror vom Datenblatt)

(Dieser Beitrag stand 2014 schon mal an anderer Stelle. Die Benchmarks auf heutigen Systemen wurden aktualisiert und ein lokaler Mirror der Bullfreeware-Liste und des Datenblatts gesichert.)